www.aib.org.uk

www.aib.org.uk

46

|

the

channel

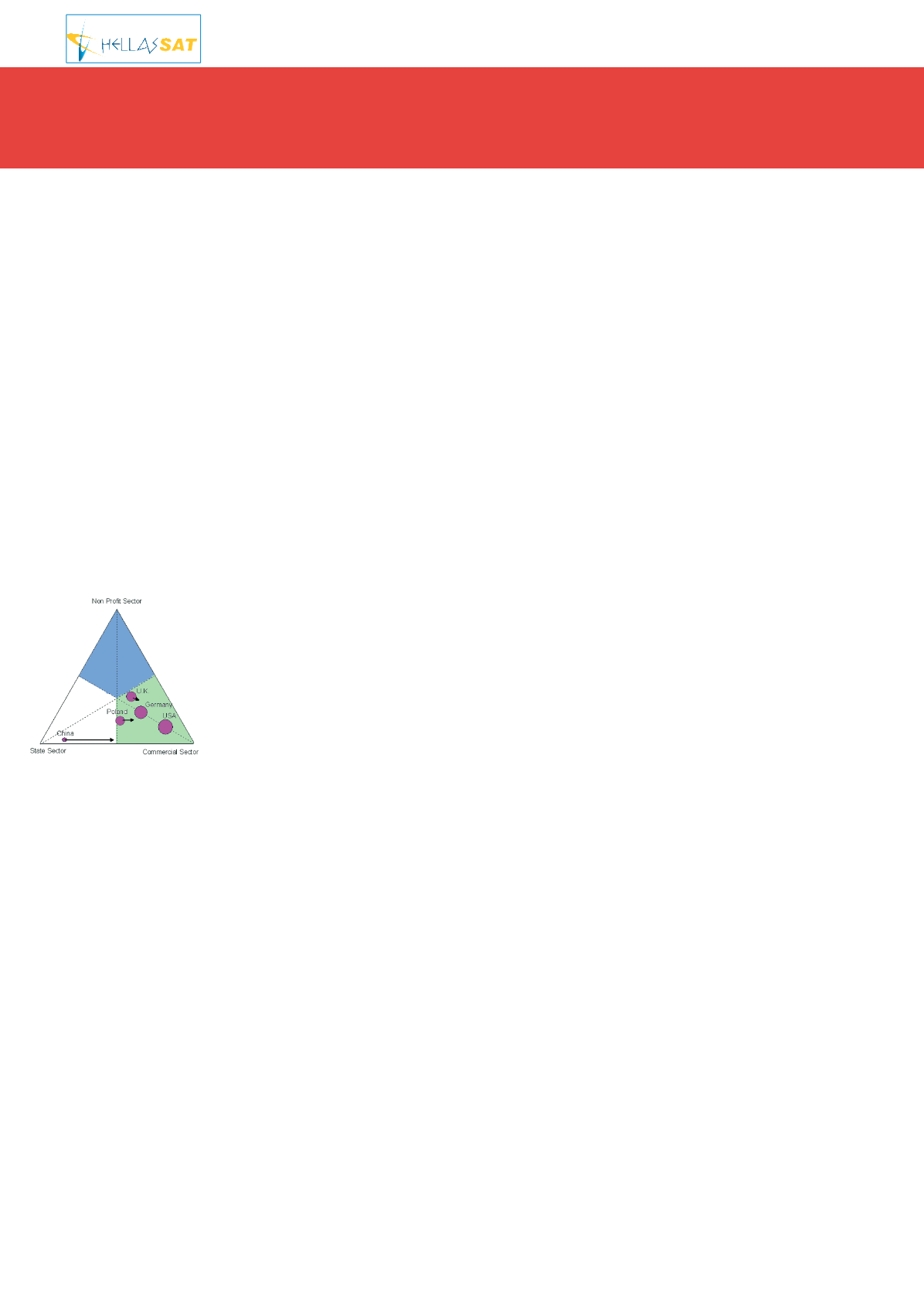

China is converting rapidly from a planned economy to a market

economy. Although the agreement on China’s entry to the World Trade

Organisation does not provide a timetable, this conversion has also reached

the audiovisual sector. Broadcasting, which in China traditionally has been

regarded and used as a tool for political propaganda, is increasingly

perceived as an industry that can fulfil the viewers’ and listeners’

programme demands – mainly for entertainment – , and as an industry

that offers great opportunities for private profit. Like in most former

communist states that go through this transformation, in China too the

audiovisual media are rapidly shifting from the state sector to the

commercial sector. In graphic form, this process can be represented as a

shift along the base line of a triangle, whose corners represent the state,

the market and the voluntary sector. In contrast to most western

democracies, non-profit organisations of the civil society are not involved

in the media in China.

Rather surprisingly, there has been a lack of

academic discussion to accompany or even

guide the media transformation that is taking

place. “Chanye Hua” (which literally means

industrialisation, but can also be translated

as marketisation) of the media is more of a

reality than a concept. “Industrial discourse”

is the keynote of present Chinese media

studies. There are several dozen books on

industrial or related topics. Business and

management have been the dominating

subjects of PhD dissertations in recent years – almost all of them are

taking a strategic perspective, especially those on media economy. As

some international scholars pointed out, ‘integrated intellectuals’ “are

riveted to functional observations at the request of those who commission

their research,” while leaving these observations “atomised and

decontextualised in relation to the implications of change in the social

and economic model”. It is no exaggeration to say that the industrial

discourse is prevalent in Chinese media scholarship, to say nothing of

those articles in professional journals. Industrial discourse advocates and

advances commercial or capitalist practices in the Chinese media.

From the industrial point of view, commercialisation is not only acceptable,

but also worth proposing and promoting. An article in the advertising

journal “Media” for instance explained “audience commodity”

phenomenon in a fairly positive way. According to the author, the

practitioners should establish a new idea of “Shouzhong Chanpin”

(audience product) because the “media are to produce audience”, “the

eventual product is the audience, while it is the customers of the audience

product that is the eventual customers of the media”. “So the operation

of the media should be guided by the demands of the eventual customers,

i.e. “party and government”, as well as advertisers, putting their needs as

the starting point of entire communication activities.” Zhu stated openly

that “the Party and govern-ment provides with social capital in exchange

for their audience products”, “the social capital, the greatest resource of

the media, is ‘permission’ “; nevertheless, the advocacy of “being guided

by the end customers of the media” and the assertion that “broadcasting

should produce only what audience advertisers need” are so candid that

it is hard to believe that this should have appeared in a country with such

a strong socialist tradition as China. To a great extent, however, this is

the very goal that some Chinese scholars are trying hard to promote, and

media practitioners are working hard to reach. As a media manager

confessed, the advertisers are our “Yishifumu” (resources of bread and

butter) so we serve themwhen they are seeking to maximize their benefits.

Yet, despite such bold and strange-sounding statements, the Chinese

television sector remains tightly constrained, at least on politically

“important” matters – ranging from the reporting of routine state functions

to the SARS epidemic. At the same time, most Chinese television stations

are pursuing their own economic interests in a rather crazy way. The

business logic means thorough commercialisation. On the one hand, the

media become more and more profitable businesses – instead of non-

profit public service; on the other hand, by making use of public resources

they become more and more self-centred, seeking commercial interest of

their own, instead of serving public interests. In fact, Chinese “media

industrialisation” is the transformation process by which the entire Chinese

media are being changed into business enterprises.

This strong belief in the potential of the market is typical of former planned

economies, and ‘the overdrive’ regarding amount and pace of conversion

is the result of an enthusiastic and uncritical evaluation of the market.

The academic discussions have not provided a counterweight to this

thinking, quite on the contrary, most scholars have promoted it. Until

now, virtually no academic voice has addressed the subject of the market’s

limits and deficiencies, which may jeopardise a public communication

that is lead by commercial media only. No voice has been heard which

explains the existence of public service broadcasting, and the extensive

regulations applying to commercial media companies – especially commer-

cial broadcasters – in most western democracies.

The joint research project which is described here attempts to bring

these aspects into the political debate. It is based on the assumption

that the opening of the audiovisual sector has both advantages and

disadvantages for China, which – in a kind of cost-benefit analysis –

can be compared and balanced to determine the optimal degree and

optimal pace of conversion. As advantages count the usual economic

benefits of free trade and the promotion of positive political and social

developments for the Chinese economy and society. As disadvantages

have to be considered: a reduction of the market share of China’s

domestic programmes as they face increasing international competition,

and the risk of too fast a transition of the Chinese economy and society

as a result of external influences by the mass media.

The question how much, how fast and by what means the Chinese media

sector should be opened (which has become an international issue since

China entered theWTO), is basically a variation on themore general question

of the appropriateness of governmental intervention in the media markets.

This includes both domestic programmes and the foreign programmes China

may (and according to theWTO ‘must’) import fromabroad.While presently

justified with the benevolence of the government, interventions can only be

tolerated if the social, political and cultural effects of a commercialisation

and globalisation of the media exceed the pace which is advisable for a

gradual and manageable (“soft”) conversion and opening of China. From

this perspective, China’s Government changes froman authoritarian regime

that does not consider the will of the citizens to a specialised agent who

serves the citizens in general, but who is – at least for a limited time period

– allowed and obliged tomodify this will, as it processes better information.

Although such a change of perspective does not necessarily have any

practical consequences for the political situation in general and for the

The

People’s Republic of China

’s huge and fast growing media market poses a particular challenge

– commercialisation is practically running away with itself. Yet the opening of the audiovisual

sector has advantages and disadvantages for China that need to be compared and balanced to

determine the optimal degree and pace of conversion. A joint research project of the Institute of

Broadcasting Economics at Cologne University, Germany, and the Beijing Broadcasting Institute

of China examines the present conversion of China’s media from a theoretical point of view. Here

project leaders

Dr Manfred Kops

and

Professor Zhenzhi Guo

explain their approach.

Co u n t i n g t h e c o s t s a n d b e n e f i t s :

C h i n a b r o a d e n s i t s T V m a r k e t s a f t e r

the channel

- supported

by